We barely speak of them and their name escapes us. Philosophy has always overlooked them, more out of contempt than out of neglect. They are the cosmic ornament, the inessential and multicolored accident that reigns in the margins of the cognitive field. The contemporary metropolis views them as superfluous trinkets of urban decoration. Outside the city walls, they are hosts—weeds—or objects of mass production. Plants are the always open wound of the metaphysical snobbery that defines our culture.[1]

This quote from the introduction to the book The Life of Plants. A Metaphysics of Mixture by Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia highlights our dual attitude towards plants, depending on the context in which they appear. The same organism can have a completely different status in various cultural or economic spaces. The example of plants classified as weeds serves as the best illustration. Biological sciences do not distinguish this category at all, so assigning a plant to it depends on the circumstances. A weed is not always a weed, and not everywhere. One floral species can simultaneously function as a medicinal plant, a decorative one, or fall into the group of Plantae Malum – “evil plants.”

All the adjectives and phrases used to describe these undesirable organisms come down to one keyword – “wildness,” understood as an extreme, untameable state, excessive fertility, uncontrollable growth. As the Concise Oxford Dictionary suggests, “weed” is a wild plant growing where it is not wanted and in competition with cultivated plants.[2] It belongs neither among agricultural crops, nor in manicured parks or gardens, where it nevertheless spreads spontaneously. Forced to adapt to life anywhere, it seizes moments of human inattention or neglect. Even a cursory examination of the behaviour of plants considered as weeds reveals their amazing ability to co-evolve with humans, develop new strategies for survival and growth. They can successfully adjust to any environment, even one that has been deeply changed by intensive farming or industry. Some of them are botanical doppelgangers, mimicking the appearance and growth rate of cultivated crops – their survival thus depends on the difficulty of telling them apart. Their greatest crime is failing to conform to human rules by appearing in places allocated a different function.

Look

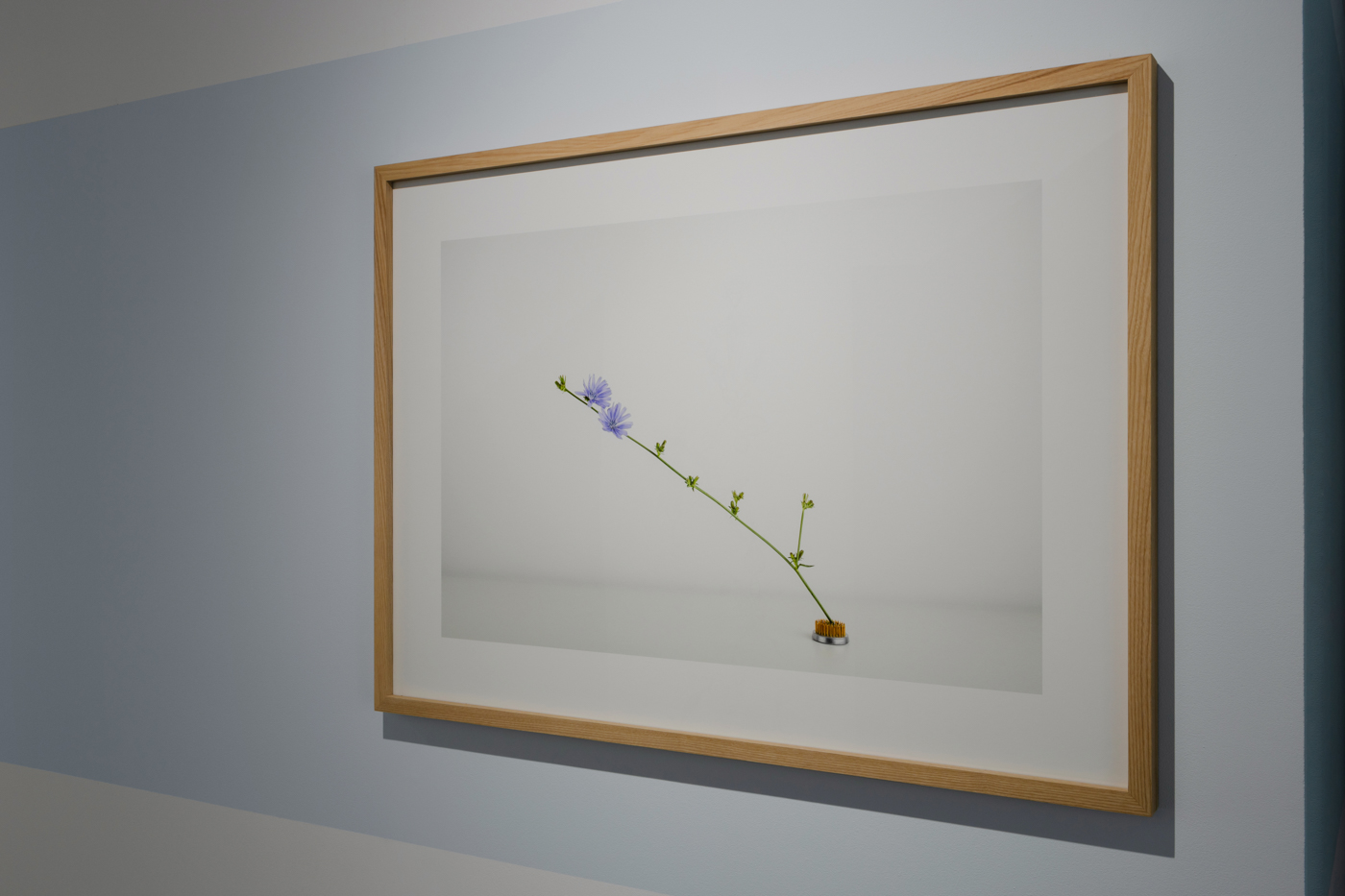

Unlike ornamental plants cultivated in gardens, weeds – Plantae Malum – are not supposed to be looked at. They deserve neither the space they take up nor our glance. We avert our eyes from them because they seem unattractive, unwanted and inappropriate. However, by selecting the right method of styling and photographing them, Anna Kędziora forces us to pay attention. She uses the kenzan to arrange the plants into a form known from floristics and allows them to fill in the entire frame. Appropriate lighting and background selection brings out their details – colour, variety, texture, shape. As a result, they turn from worthless waste into tenderly portrayed organisms. Are these artistic gestures enough to make Plantae Malum beautiful (Plantae Pulchrum), and therefore good?

Word

The language of talking about weeds uses dualistic, stigmatising terms and metaphors focusing on the undesirable features of these plants and their relations with other plants and with people. It leads to demonization and consolidates our stereotypical way of thinking about them, unambiguously demonstrating the human fear of losing control and deliberately blocking any ethical reflection on them. Being aware of the power of language to shape our consciousness, Anna Kędziora uses it in a very perverse manner. In the presented recording, she does not reveal the names of the plants featured at the exhibition; instead, she reads out their physical descriptions taken from the atlas of weeds. The detailedness of these entries has a specific function – to enable precise identification and effective elimination of the unwanted specimen. However, the omission of their names results in the creation of a huge entanglement of random words, all the more so since neither the photographs nor the wax prints are labelled. How can we then know what we are actually looking at? Deprived of a clue in the form of a name, we are lost, forced to fall back on our own intuition. The recited words, with a surprisingly large number of diminutives among them, quickly disappear. The woman’s voice makes them sound poetic. Is this the way to talk about weeds?

Wildness

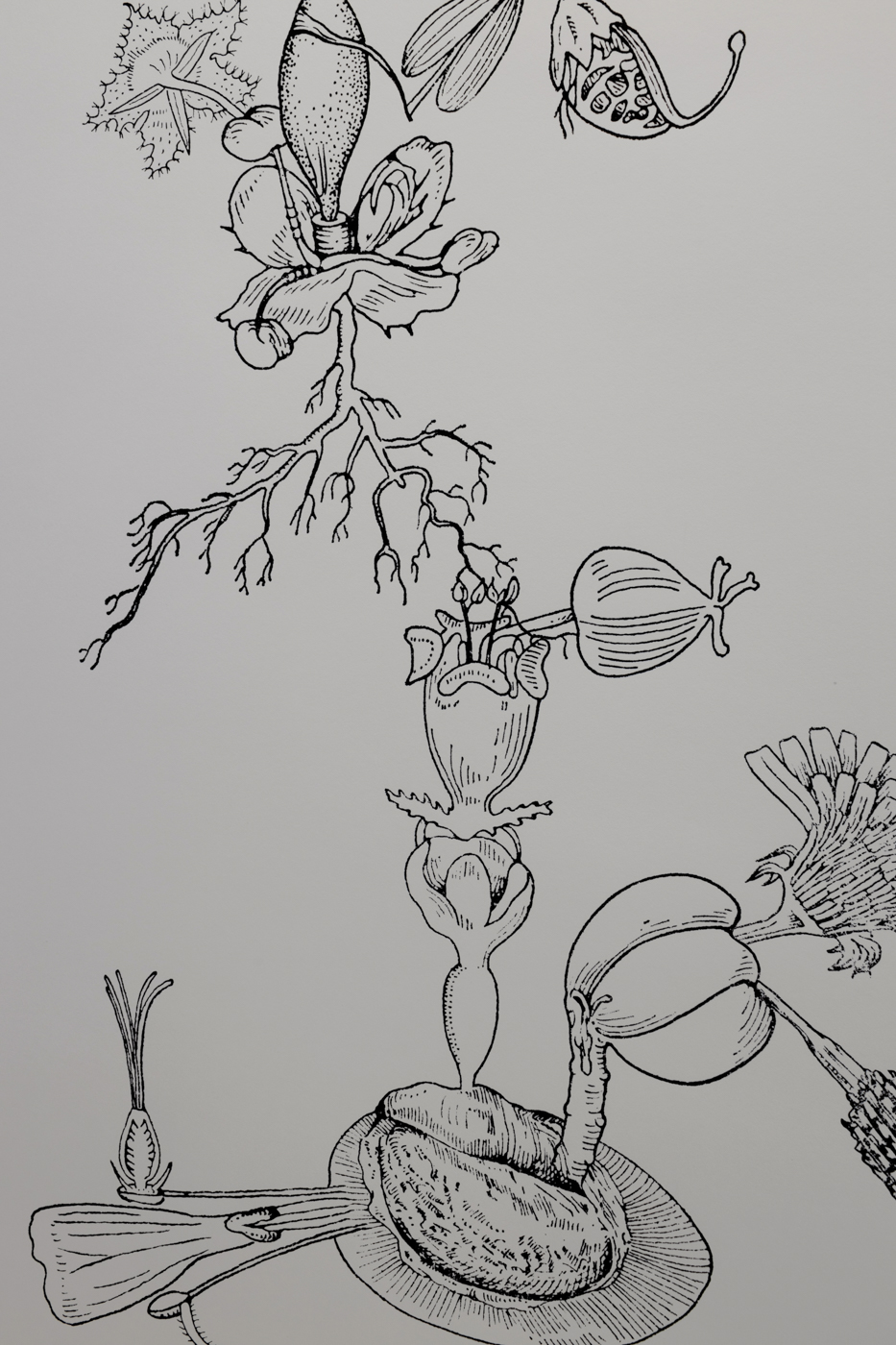

Anna Kędziora makes no attempt to arrange the featured plants into a compact, structured set. Her collection of beeswax prints seems unsystematic and chaotic; sometimes only a fragment of a plants is visible, with the details missing. We have to rely on our memory and imagination not to recognise the plant, but to recall how it would look in a wild meadow. The graphic hybrids, based on botanical drawings of weeds, are the most unruly. In the colonial world, plant hybrids had a special status. Many of them were of significant economic value, demonstrating the effectiveness of innovative breeding methods. In general, no hybrids were created that would be harmful to crops. That is why I perceive Anna Kędziora’s gesture as liberating. Plantae Malum have escaped – from the plant atlas, from ugliness and oblivion, throwing off the shackles of linguistic clichés and definitions. Will they become even a little more noticeable or wanted, will we let them be (themselves)? If not, one more question remains: Is it possible that, as a result of environmental degradation, the plants that are considered weeds today will ever be protected as endangered?

[1] E. Coccia, The Life of Plants. A Metaphysics of Mixture, Wiley-Blackwell, 2018, p. 3.

[2] The Concise Oxford Dictionary, 10th edition, edited by Judy Pearsall, Oxford University Press, 1999.